NATIVE AMERICAN HISTORY OF HOUSTON COUNTY

Houston County in southeast Minnesota lies in the driftless area. The area was largely untouched by the last glacial advance. As the glaciers melted, water erosion formed the distinctive high bluffs and deep valleys found in the county. The area was desirable for prehistoric people to settle. Rock outcroppings provided chert and other materials used for tools and weapons. Abundant prairie and woodland with streams and rivers provided materials for homes and an abundance of food.

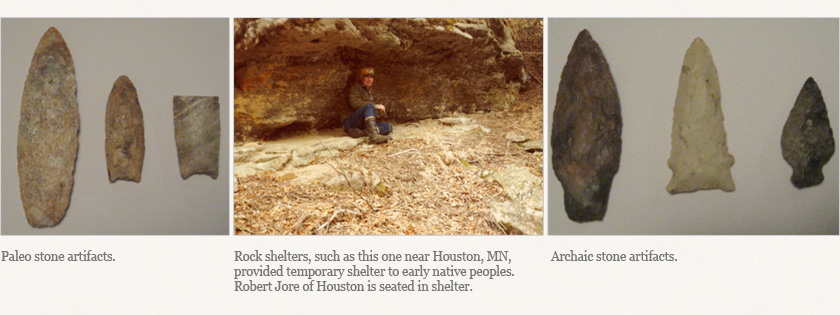

The first prehistoric people arrived in Minnesota as early as 13,000 years ago. Archaeologists call them Paleo-Indians. These nomadic peoples were big-game hunters who followed animal herds and used temporary housing. No permanent habitation site of the Paleo-Indian era has been found in the county but a few lanceolate-shaped points from Paleo-Indian spears indicate their presence in the area. Climate change and the extinction of many large animals hunted by the Paleo-Indian people led to adaptations and changes in their survival tactics. These cultural adaptations lead to the next era in prehistory.

The Archaic Tradition started about 9,000 years ago. Archaic people adapted to the new environments that developed after the end of the Ice Age. In addition to hunting and fishing the archaic people gathered nuts, berries, and other foods from their surroundings. Their tools included spears tipped with stone points and the use of copper by groups living around the Great Lakes. The Archaic people were able to live in larger groups, on semi-permanent sites. Archaic sites found in Houston County are often located on the sandy knolls along creeks and rivers. These small sites may have been used as hunting or gathering camps at various times throughout the year.

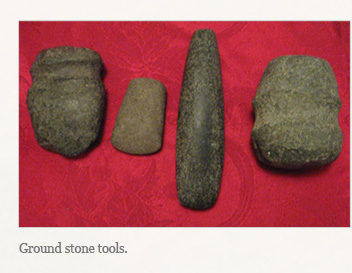

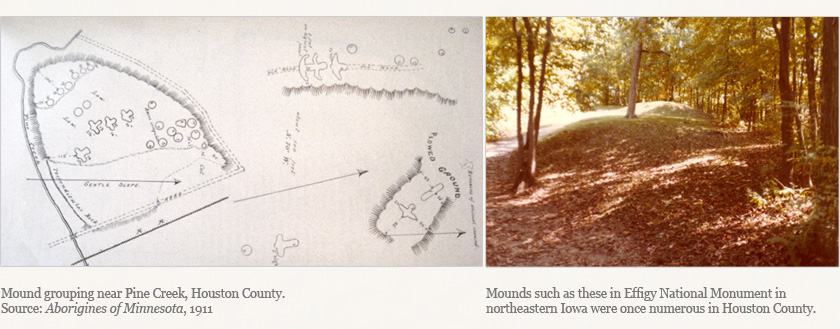

The next era, termed the Woodland Tradition, began about 3,000 years ago. The distinct traits of the Woodland peoples were the development of pottery and the building of mounds. The earliest known pottery in southern Minnesota was found at the La Moille rock shelter near Winona. This site had been used as a fishing camp in late Archaic and early Woodland times.

It is thought that Minnesota once contained over 10,000 mounds. Few still exist today. Several hundred were located in Houston County along the river bottoms. The major mound groups were in the areas of Hokah (30-40 mounds), La Crescent (62 mounds), Pine Creek (24 mounds), a site near New Albin, Iowa (11 mounds), and Winnebago Creek (40 mounds). The Hokah group contained a bird effigy measuring 87 feet long with wings spanning 225 feet.

The Woodland Tradition came to a close in southeast Minnesota by about 1000 A.D. The next era is called the Mississippian Tradition and was distinguished by agriculture and cultivation of maize (corn), beans, and squash. Hunting, fishing, and wild plants provided additional food. Mississippian pottery is unique in that the tempering material used was crushed clamshell instead of the pulverized stone which was found in earlier pottery.

Many of the sites found in Houston County are quite late as evidenced by the early trade items found in them. Archaeologists call the late pre-contact and early historic sites in southeast Minnesota and northeast Iowa the Oneota culture. Some excavated Oneota sites in Houston County date to the middle of the 17th century. It is not known when the Oneota left this area but by the early 1700s they had moved south and west. Historically they became the Iowa, Otoe, Missouri, Ho-Chunk (Winnebago), and other related Native American tribes.

The Sioux or Dakota Indians were found in much of Minnesota. The Sioux were comprised of seven distinct bands. One of them, known as the Mdewakantonwan Sioux, made camps along the Mississippi River, including in southeastern Minnesota near Winona. Their leader was Wabasha (or Wapasha). He retired to his favorite camp on the Root River and died there in 1806. In 1851, through treaties, the Sioux relinquished their claim to the lands in the southern half of Minnesota.

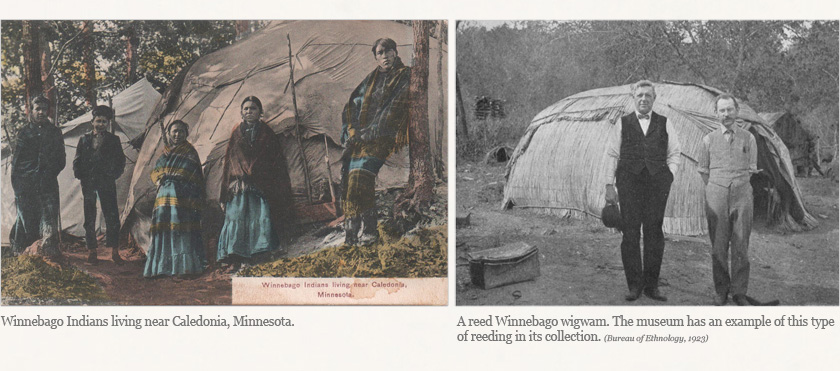

The treaty of Prairie du Chien in 1830 established a 40 mile wide tract of land called the Neutral Ground. It was formed by the cession of two 20-mile strips of land; one from the Sioux and the other from the Sac and Fox. The major portion of the tract was in Iowa but a small part included a sliver of Fillmore and Houston Counties. The Winnebago, known today by their ancestral name, Ho-Chunk, had relinquished their land east of the Mississippi River in 1837 and were given lands in the Neutral Ground. They were moved there in 1840.

The Ho-Chunk were moved several more times following the Dakota Conflict of 1862. In 1865, they were given lands in northeast Nebraska. This reservation still exists today. Through the years small family bands moved back to their original homelands in southeast Minnesota and western Wisconsin. They settled near towns and along the Root and Mississippi Rivers. They preferred to live independently in the traditional wigwam or in abandoned buildings. They had contact with white settlers to trade for supplies and sell their wares. They are noted for their crafts and especially their basketry. The black ash trees that grew along the river bottoms were favored as the weaving material. The names of numerous area towns testify to their presence in the area.

In 1939 and 1940 tax exempt status was given to several tracts of Indian owned land setting up two small Ho-Chunk reservations in Houston County. One area is located south of La Crescent and the other is located between Hokah and Brownsville.

Archaeological work in Houston County was done starting in the late 19th century with the surveying of mounds by Theodore H. Lewis. The next professional excavations started in the early 1940s. Excavations have continued through the decades precipitated by road widening projects or university research projects. The discovery of burial and village sites has revealed Houston County’s rich Native American history.

Suggested Reading

1. Faldet, David S. Oneota Flow: The Upper Iowa and Its People, University of Iowa Press, 2009.

2. Mahan, Bruce E. Old Fort Crawford and the Frontier, Prairie Du Chien Historical Society (reprint) 2000.

3. Theler, James L. and Boszhardt, Robert F. Twelve Millennia: Archaeology of the Upper Mississippi River Valley, University of Iowa Press, 2003.

4. Nilles, Myron A. 1660-1853 A History of Wapasha’s Prairie (Later Winona, Minnesota), Winona County American Bicentennial Committee, 1978.

5. Blaine, Martha Royce. The Iowa Indians, University of Oklahoma Press, 1979.

6. Van Schaick, Charles. People of the Big Voice: Photographs of Ho-Chunk Families, Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2011.

7. Arzigian, Constance M. and Stevenson, Katherine P. Minnesota’s Indian Mounds and Burial Sites: A Synthesis of Prehistoric and Early Historic Archaeological Data, Minnesota Office of the State Archaeologist, 2003.

8. Winchell, N. H. Aborigines of Minnesota, reprint by Gustavs Library, 2007.

9. History of Houston County, Minnesota, Houston County Historical Society, 1982.

10. Boszhardt, Robert F. Deep Cave Rock Art in the Upper Mississippi Valley, Prairie Smoke Press, 2003.

11. Anfinson, Scott F. A Handbook of Minnesota Prehistoric Ceramics, Minnesota Archaeological Society, 1979.

12. Johnson, Elden. The Prehistoric Peoples of Minnesota, Minnesota Historical Society, 1978.

13. MuCune, Ivy. Winnebago Baskets, self published, 1976.

14. Mason, Carol I. Introduction to Wisconsin Indians: Prehistory to Statehood, Sheffield Publishing Company, 1988.

15. Burke, William J. The Upper Mississippi Valley: How the Landscape Shaped our Heritage, Mississippi Valley Press, 2000.

16. Bailey, Edwin C. Past and Present of Winneshiek County, Iowa, Anundsen Publishing Co. (reprint).

17. Nienow, Jeremy L. and Boszhardt, Robert F. Chipped Stone Projectile Points of Western Wisconsin, Mississippi Valley Archaeology Center, 1997.